The apex of a summer’s magic hour when everything is covered in a haze of sedation, the wee hours of the night as you speed down the highway with nothing but the static sounds of the world buzzing around you, the afternoon you sit atop a room in September and watch the world fall to piece—all moments in time that fall into the realm of the ineffable. You live through them and remember them in feeling rather than words, in tastes and textures, occupied by smells and sounds that remain inside you in a way that’s beyond articulation. And it’s in those moments, existing on that wave of existence that William Basinski’s music lives and breathes. But as all things, it’s also quietly dying one moment at a time. As you fall under the spell of his looped melodies, you can almost see the dust collecting and falling down around you like ash. It’s as beautiful and profound as it is heartbreaking and melancholic, and there’s never enough.

For over twenty years now, avant-garde electronic composer has been creating his own unique world of sound, but it’s only in last decade that the world pricked up their ears. “It took a while for people to get it,” he says, “I tried to release things in the eighties but there were no takers. When The Disintegration Loops happened, it just hit. It was something for critics to dig into and launched everything.” Growing up in Texas, Basinski attended prestigious music schools and was classically trained in clarinet and jazz sax but quit to “play around with tape loops.” After being greatly inspired by Brian Eno’s Music for Airports and the work of Steve Reich, Basinski began experimenting and investigating just how far he could go. “When I started to get encouraging results, I just kept going,” he says. “The piano variations pieces, really…all those loops came from a really bad composition I was trying to do on the piano. I did cut ups randomly looped them and then I started experimenting with those on the machine and just layering. Then I really started getting the results I was dreaming of.”

When asked about the deeply sensory and emotional effects of his work, Basinski says, ““I don’t know if that’s my music or your synesthesia, but when it’s working, it should work like that. It blows my mind. I don’t know how I did any of this stuff.” With all of his music, whether it be his piano variations, El Camino Real or The Disintegration Loops, Basinski plays with time in such a way that it almost has an amnesiac effect—you lose a sense of place and time, falling down into the abyss. “That’s what we want to get to, the time machine, the space station,” he says. “In the concerts, I usually do one long set because the whole point is to try and get out of this body and this worry and this nonsense and just take a little vacation, fall in. And forty minutes can go by and it feels like five, so that’s the ideal situation. It’s like meditation, you have some relief, you sort of go back into the womb.”

But for all his creations, it’s The Disintegration Loops and the stunning process from whence they came that’s shed light on his years of creation. “I was at a point where I didn’t have any work and I was agonizing over the fact that I was about to be evicted and had no money but it was a beautiful day and I said just get back in there, use this time and continue where you left off with archiving these loops,” admits Basinski on the process. And what happened next was as much as an accident as it was an act of fate. “So this loop comes up and I said, ‘This is perfect and just what I need right now,’ and went to the synthesizer and set up a counter melody and random arpeggiating French horn sounds. It was working really nicely, and I started recording it and sitting there monitoring it, and I went to make some coffee and when I came back, I noticed something was changing…I looked at the tape deck and could see dust on the tape pad, and the tape was disintegrating as it was going around and around and around,” Basisnki explains. “So I was just like, Oh my God, what’s going to happen? I checked to make sure it was recording; it was, and by the end of the CD, it had pretty much disintegrated. I was pretty blown away so I put the next one on and in it’s own time and it’s own way the same thing started happening.”

The result was an epic five-hour work that in and of itself was a work of nature—a sonic apparition of death and decay of what once was, transforming and giving birth to something new. “I had no idea what I was going to do with it, but I called all my friends and said, ‘Get over her! You won’t believe what happened.’ They came over, and my one friend Howard Schwartzburg said, in his Coney Island accent, ‘Billy, oh my gawd! This is it, you’ve done it!’ We just kind of jumped for joy.”

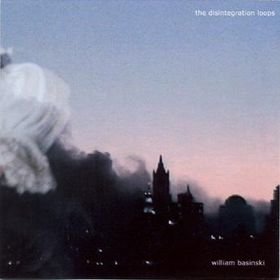

All this occurred late into the summer of 2001, a time of silence just before the world was about to change. On September 11, Basinski was planning on heading down to the World Trade Center to apply for a job when he awoke to see that the towers had been hit. “Everyone that was in New York knows what it was like to be there and not just see it on television. It was shocking and horrifying, and it just got worse and worse. A friend of mine and I had just quit smoking, but that afternoon, after we sat there on the roof and watched both towers collapse, we said, ‘The world was ending. We’re going to get cigarettes.’ So I went to go get some cigarettes and I also bought a videotape. My friend had her camera up on the roof, so we came home and put the loops on really loud and just listened to it and watched what was happening. We didn’t know what was going on, so we listened to the music.”

The next morning, Basinski paired his music, “dlp 1.1,” with the tape his friend had shot. “It was just this incredible elegy,” Basinski says. “I decided I couldn’t make sandwiches; I couldn’t do anything except my work. This is all I can do.” The four frames from the film wound up as the four album covers as Basinski released the pieces one by one. The Disintegration Loops, although not made in direct correlation of 9/11, possess within them a sense of hopelessness and fear as well as the feeling of something grand—something happening in the world that’s bigger than everyone else.

Last year, for the tenth anniversary of September 11, the music was used as part of a commemorative performance held at the Temple of Dendur in the Met and has since been translated into further orchestral pieces by Maxim Moston. This fall, the piece will be inducted into the National September 11th Memorial & Museum. Now, to celebrate the tenth anniversary of The Disintegration Loops, Temporary Residence has put out a massive limited-edition box set containing all four volumes, rare recordings of the live orchestral performances, the piece remastered on vinyl for the first time, the extremely rare The Disintegration Loops film, and a 144-page full-color coffee table book.

Basinski’s work is the ghost of something that once was, and as it evolves and takes shape in these different forms, it’s as if it just keeps haunting and creating an endless loop of its own.

Published in 2012 for BlackBook Magazine